***We are currently in the final push to prepare and release the second issue of the interdisciplinary journal Martial Arts Studies. This will be a themed issue examining different aspects of the “invention of the martial arts” in a wide variety of settings and time periods. Paul Bowman and I are very excited about the selection of articles and reviews that we will be presenting later this week. But at the moment all hands are needed for the final round of proof-reading, editing and otherwise preparing the issue for its impending release. As such we will be revisiting an important discussion from the archives, touching on the prehistory of the Wing Chun mythos, for today’s post. Enjoy!****

I propose to speak on fairy-stories, though I am aware that this is a rash adventure. Faerie is a perilous land, and in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold. And overbold I may be accounted, for though I have been a lover of fairy-stories since I learned to read, and have at times thought about them, I have not studied them professionally. I have been hardly more than a wandering explorer (or trespasser) in the land, full of wonder but not of information.

J.R.R.Tolkien. “On Fairy Stories.” 1939.

Introduction

These are the words with which J.R.R. Tolkien, the distinguished author and professor of English, began the 1939 Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St. Andrews. The entire essay is well worth reading. Tolkien had devoted considerable thought to the growth and evolution of stories and he was well aware that they take on a life of their own. If we were to substitute the words “martial arts mythology” for “fairy stories,” the preceding quote sums up many of my feelings towards our own subject.

The early Republic of China period generated an enormous body of new martial arts folklore. As a community we are still identifying, contemplating and digesting a lot of this material. Some critics, upon learning that the wine they drink is not of the vintage that they first assumed, are prone to dismiss the entire exercise as a fraud. They wish to get as far back into the “authentic martial arts” as they can and often see the relatively late Republic period as one of hucksters “diluting the arts.” Yet in most instances the wine actually tasted pretty good before anyone stopped to take a closer look at the label.

Herein lies our dilemma. Many of the elements of the traditional arts that are the most popular today, generating the most excitement with audiences in both the East and the West, are not the ancient and “authentic” material, but rather the later innovations of the 1920s and 1930s. If we were to simply throw out everything that was “new” and return to some arbitrarily dictated “golden age” (1800, 1600, 1100, 500…….) we would not just discard a lot of recent marketing, but also much of what attracts people to the traditional Chinese martial arts in the first place.

Consider for example the Wing Chun creation myth. Wing Chun is one of Southern China’s more recent boxing styles. Its mythology claims that the arts dates back to the 1720s at the earliest, whereas most hand combat schools prefer to situate their genesis at an even earlier point in China’s long history.

Almost all of these claims are massively exaggerated. Yet ironically the order of the points on the timeline is approximately correct. Wing Chun is a younger art. Its first organization probably dates to the middle of the 19th century and it was later reformed in the Republic period.

This relative newness has done nothing to prevent the art from generating a rich body of folklore. Its mythology even has some interesting and unique features. For instance, students often marveled that Wing Chun is one of the few martial arts from China to be “invented by a woman.”

Nor does this association with the feminine principal appear to be some sort of fluke. Both the creator of the art (Ng Moy, a survivor of the destruction of Shaolin) and her student, (Yim Wing Chun, who was forced to fight a challenge match to prevent a forced marriage) were women. It was only in the third generation that male students entered the art.

The gender of these two individuals had a profound effect on the development of Wing Chun. Ng Moy began with the standard Shaolin arts, but after becoming a recluse in South West China she had a vision of a crane fighting a snake. Only after this revelation was she able to combine both evasive movements and structured direct attacks in a way that would allow a smaller fighter, like a woman, to overcome a much larger and stronger opponent.

Of course Ng Moy was a master of the martial arts. Her abilities are the stuff of legend. The real question was whether this system could be taught to a new student, one without any physical advantage or extensive training in the martial arts?

The story of Yim Wing Chun provides us with the perfect proof of concept. The older woman takes the young daughter of a tofu merchant to her mountain retreat where she initiates her into the mysteries of her art. Upon descending from the mountain the young girl promptly proves that a smaller person can defeat a much larger opponent by employing the proper principals and structures. Fittingly it was Yim Wing Chun who gave her name to the art.

Modern Wing Chun students still love this story. I have provided only the briefest outline of it above, but it is rich in meaning and symbolism. It is amazing how much understanding a thoughtful reader can pull out of it.

The only problem is that this myth is generally read as a historical account. In fact it is a piece of popular literature. I say literature, rather than folklore, quite intentionally. This is not the sort of thing that orally evolved over a long period of time, at least not in its present form.

Rather, some individual, probably working in the 1930s, sat down and appropriated certain stock characters from Wuxia martial arts novels that had been recently published in the area, possibly combined them with older traditions from the White Crane or Hung Gar clan, added in what might be an authentic (or partially-authentic) genealogical name list, and consciously composed the story that we have today. I have already discussed the details of this process (particularly as they apply to the evolution of the character Ng Moy) elsewhere.

Nevertheless, this story was not created in a vacuum. If it was it would be easy for students of Chinese martial studies to ignore it. One could simply write it off as a flight of fancy or as a particularly effective advertising gambit.

I do not think that this would be very wise in the present case. To begin with, it is an interesting (and fairly sophisticated) example of the sort of storytelling that was going on all over the hand combat community. The martial art story telling tradition was not new. There had been a vibrant market in cheaply printed martial arts novels throughout the late Qing. But it was usually authors and publishers who generated the mythology. Martial artists seem to have been more concerned with their military, law enforcement, operatic or criminal careers.

As the nature of the economy changed in the early 20th century the creation of public commercial hand combat schools became a possibility. Each of these newly created institutions discovered that they needed the sort of historical authenticity that can only be provided by a really compelling backstory. Schools from earlier periods may have had their own backstories as well, but most of the ones that we possess now date from the early years of the 20th century, or just a little earlier.

Other things changed beyond the sheer volume of stories that were published. New types of characters emerged. One of the most interesting things about the Republic period literature was the sudden proliferation of female heroes in these stories.

Traditionally wuxia novels, like the martial arts themselves, had been a male dominated domain. It is true that there are occasional references to female knights-errant in some of the older works. There is even a female hero in the classic novel Water Margin. But these figures were very much the exception that proved the rule.

Very rarely did women appear in older martial stories and when they were mentioned it was almost never in a heroic capacity. Instead they were often used as a malignant plot device to give the male hero a chance to “restore the proper social order.”

All of this begins to change in the Republic period. Certain reform movements (most notably Jingwu) began to actively teach and cultivate female martial artists, giving them an increased prominence in society. But even before that there was an explosion of female characters in martial arts stories. These characters manage to break out of the stereotyped roles of “virgin-martyr” and “femme fatale” and become actual heroines. They also appeared in a wide range of stories, from the comic to the historic and even the tragic.

This literary trend should be remembered when reading the story of Yim Wing Chun and Ng Moy. There are certainly older stories of female warriors, but these two characters were imagined and put to paper at the height of the popular interest in martial arts heroines. The very fact that the Wing Chun creation narrative focuses so closely on a pair of female warriors, and is so self-conscious in its discussion of how a smaller and weaker “female” body could defeat a stronger and larger “male” one, is yet another piece of circumstantial evidence that we are dealing with a literary creation of the early-mid Republic of China period.

The thing that I find most interesting about all of this, and which most discussions tend to ignore, is that a story which was explicitly composed to address the tastes and needs of individuals in Southern China in the 1930s can continue to speak so strongly to individuals on the other side of the world today. That is a remarkable achievement and one to be admired.

Martial arts fiction is actually much more complicated than something like wine, which simply improves with age. It is more like a gourmet soup. It has many ingredients, some of which blend imperceptibly together, while others stand out providing high notes and a sense of depth. To the uniformed it may look as though the chef simply pours everything into the pot and stirs, but there is usually some very important selection that goes into a good recipe, or story.

Is it possible to look at these stories and guess what ingredients went into them? Can we understand how the 1920s narratives of female warriors were constructed and why they struck such a cord with audiences? Certain large elements within the Wing Chun narrative are easily identified, though it is hard to ascertain what their original form was before they went into the pot.

The female creator of Yong Chun White Crane can be seen in both the later stories of Ng Moy and Yim Wing Chun. Further, the Cantonese Opera Singers with their ill-fated rebellion is easily distinguished.

Professor Tolkien at Oxford University. Incidentally this is what an academic office is supposed to look like!

But what else can we detect floating in the broth? What sorts of ideas about female warriors were common in popular culture and why did they start to rise to the top at the end of the Qing dynasty? In the same essay that I quoted earlier Tolkien warns that such an enterprise is difficult and possibly not as profitable as it might be hoped:

“…with regard to fairy stories, I feel that it is more interesting, and also in its way more difficult, to consider what they are, what they have become for us, and what values the long alchemic processes of time have produced in them. In Dasent’s words I would say: ‘We must be satisfied with the soup that is set before us, and not desire to see the bones of the ox out of which it has been boiled.’”

In both literary and ethnographic terms his advice is sound. Once we have separated our dinner into its various components it will no longer be “soup.” In the quest for the bones we will have lost some of the emergent properties that made these stories so powerful and interesting to us in the first place. Still, to the historian bones can be a useful thing.

Tang Saier: Buddha Mother and Rebel Warlord

David Robinson, in his book on Ming social history (Bandits, Eunuchs and the Son of Heaven, Hawaii UP, 2001), argues quite convincingly that we have generally underestimated the importance of violence in daily life during even relatively peaceful eras of dynastic history. China’s history was literally written by Confucian scholars who saw the word in deeply ideological terms. They sought to promote a certain vision of the past so as to guide the decisions of rulers in the future. In their narrative violence is a tragic aberration, or the result of social disorder in either society or the court.

Robinson instead argued that violence was a regular feature of daily life in late imperial China. The government and the military were chronically underfunded and understaffed. Without the cooperation of local “men of action” it was impossible to accomplish any task from clearing the road of bandits to collecting tax payments. There was an actual “economy of violence” that stretched through all levels of society, from the highest eunuchs at the court down to village thugs. This market in violence was just as complicated, and essential to the good governance of the kingdom, as any other aspect of the economy.

It should come as no surprise then to learn that the sphere of women often intersected with the economy of violence. The Venn-diagram of China was simply not big enough to keep these two massive cultural areas from intersecting. Then as now women were often victims of violence. But at other times they were actually independent agents in these destructive cycles.

Consider for instance the social upheaval caused by the Yongle Emperor (1360-1424). Hongwu, the first Emperor of the Ming dynasty, left a complicated succession situation at the time of his death. After his first son preceded him, the Emperor decided that the throne should go to his primary grandson (reign title Jianwen), rather than his own next inline surviving son. The younger, militarily minded, son of Hongwu would not let this slight pass, especially when Jianwen started to eliminate his powerful siblings. After a successful military campaign Yongle was able to oust his nephew and capture both the capital and the throne for himself.

Unfortunately it was easier to capture the physical space occupied by the capital than the hearts and mind of its inhabitants. Many important officials flatly refused to serve the new Emperor, and were murdered (along with their families) as a result. In an attempt to consolidate his legitimacy, and address long standing tactical problems, Yongle ordered that the capital be moved north to Beijing.

This too was easier said than done. Beijing had been devastated by disease and disaster. It needed to be rebuilt. New walls and a grand palace (the Forbidden City) had to be constructed. Nor could this be done in an economic vacuum. Other northern economic and population centers also had to be upgraded to shelter and service the new capital. Even the Grand Canal had to be restored.

This was a massively expensive undertaking. To finance it the tax role needed to be restored and huge amounts of waste-land had to be reclaimed and tilled. Vast numbers of workers were necessary to carry out all of these tasks. Labor was the one item the one item that the Yongle Emperor had in relative abundance. Nevertheless, tapping those reserves turned out to be more expensive than he imagined.

In order to carry out the various rebuilding projects large numbers of peasants from poverty stricken, and notoriously rebellious, Shandong province were pushed into government labor corvees. These demands upset the economic and social situation in the area, leading the normal banditry and millennial movements to morph into something much more dangerous, open rebellion.

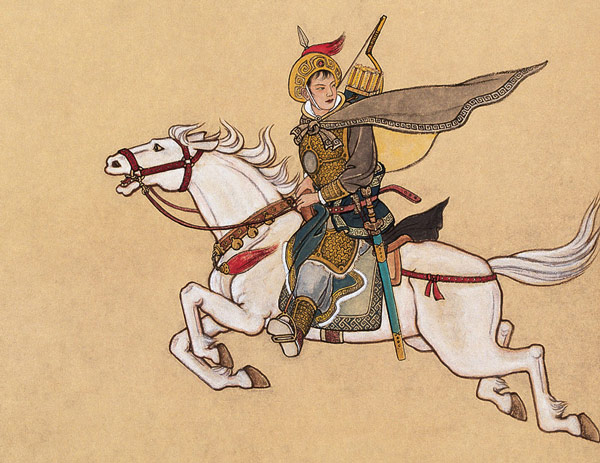

A painting depicting Tang Saier opposing the troops of the Yongle Emperor. Note the paired sabers, favored by a number of China’s literary heroines.

One of the critical leaders of this movement was Tang Saier, a woman. Along with her husband she was successful in leading a group of rebels in the capture of a number of walled cities in Shandong starting in 1420. In each case the imperial representatives were murdered and her band gained more followers. Eventually she commanded a rebel army that numbered in the tens of thousands.

Tang Saier used what social roles were available to her in crafting her public political personality. On the one hand he posed as a self-styled female knight-errant. Like other warriors from this mold she was seen as fighting both against injustice and for the establishment of the proper social order. And by all account she was an active and successful military leader.

Prof. Victoria Cass has pointed out that there was also another aspect to her persona. She was widely seen as a religious adept. As the de facto “god-mother” of the area’s White Lotus movement she was expected to display the signs of mystical (and even magical) attainment. Stories circulated that enemy weapons could not harm her, or that she had come into possession of her martial skills when she found an arcane text and a magical sword in a mountain cave. Some claimed that she was chosen by the Primal Mother of the Nine Heavens, the problematic patron saint of female mystics, recluses and warriors. Others, including her troops, called her “Mother Buddha.”

This mixing of the martial and magical is typical for millennial uprisings in northern China. The same basic patterns will reemerge in the rebellions of the late 19th century. However, Prof. Cass points out that the thematic mixing of the mystic and martial archetypes was much more common in female warriors and military leaders than male ones. To their followers these miracles were signs that the leader was a true adept who followed the dictates of heaven. To the state they were evidence of dangerous sorcery and a threat to the established social order that went well beyond the purely military potential of such groups.

The Yongle Emperor may have been particularly vulnerable to the challenge posed by a movement like Tang Saier’s. Clearly he would have remembered that his own grandfather used his leadership of a millennial army to seize control of the state and establish his own dynasty. Further, Yongle was moving the capital to the north at a time when his legitimacy was still a sore spot. He showed little restraint in crushing the new rebellion in Shandong.

What happened next was remarkable. The imperial army was able to destroy the poorly armed, fed and trained rebels. Yet after an extensive search they failed to catch Tang Saier.

Obviously the first rule of fighting a messianic figure is not to let her get away, thereby establishing expectations of an imminent return backed by heavenly armies. In a symbolic sense the legitimacy of the Yongle Emperor’s reigns was based on his ability to find and punish dangerous heterodox leaders who threatened the kingdom with chaos. This is what it meant to be the “Son of Heaven.” Yet in this case the search yielded nothing.

The Emperor was incensed and decided (reasonably) that the only way that Tang Saier could evade imperial justice for so long was if someone was hiding her. Of course there were not that many bases of independent power in the poorer regions of northern China. The gentry in the area was weak, and most of the big rebel bands had just been crushed. That left the temples and monasteries, institutions which the state viewed as potentially problematic at the best of times. It would have been all too easy for Tang Saier to blend into the poorly regulated local religious landscape as either a Daoist or Buddhist adept.

The Emperor’s agents turned their attention to the area’s religious institutions. On imperial orders the region’s entire population of nuns (both Buddhist and Daoist) was put under arrest and brought to the new capital for questioning. It was illegal to take up a religious vocation without a license from the government. These were highly regulated and generally only given to the educated and orthodox. One can only assume that a huge number of “unofficial” Buddhists and Daoists clergy were returned to the tax role, as well as the land owned by their temples and sanctuaries. This sweep of the local religious landscape would have been a great help to the Emperor’s efforts to establish de facto social control over northern China.

The one thing it did not accomplish was locating Tang Saier. Like the later “Elders of Shaolin” and Ng Moy, she successfully evaded the imperial dragnet and was never heard from again. This was a major embarrassment for the government. An individual bandit warlord or rebel might evade capture and no one outside of the effected region would really know or care. But the move against Shandong’s religious community was an event on such a massive scale that it could not be kept secret. Now everyone knew who Tang Saier was, and they knew that she had gotten away.

The wife of a Chinese general circa 1810. Notice that both she and her female attendant are armed. Source: Digital Collections of the New York Public Library.

The Literary After-life of Tang Saier

There is a lot we do not know about Tang Saier. It turns out that much of what we know about the birth, death and lives of important rebel leaders is glean from imperial records. These in turn reflect interrogation and trial documents as well official reports. Given that she was never captured we actually don’t have a clear idea of when she was born or died.

This lack of basic biographical facts has not stopped a rich literature, some political, but most fictional, from springing up around her. The Ming vilified her as a witch and sorcerer. Qing historians reevaluated her legacy, and Republic and later Communist historians noted that she fought against what amounted to legalized slavery.

Tang proved to be too charismatic and mysterious a figure to ever disappear from popular discussions, either at the level of local folklore (where she is still remembered) or in the more elite literature. Ironically an “outsider” like the rebel Tang Saier became the perfect vehicle for a certain group of 18th century Ming loyalists to criticize the political and social conventions of their day.

The first (surviving) novel about Tang Saier was published in 1711 by Lu Xiong. Lu was highly educated but on the orders of his father (a Ming loyalist) he never sat for the imperial exams, and instead became a physician. Apparently Lu shared many of his father’s political views and he employed Tang’s criticism of the Yongle Emperor as a screen to comments on much more recent events without running afoul of the censors.

His novel, titled Nuxain Waishi (The Unofficial History of the Female Immortal), was shared widely in manuscript form before it was published and it had many admirers. The first edition appears to have been fairly successfully. Unfortunately, the novel was closely tied to a critique of events in the opening years of the 18th century, and as such it was not widely read by succeeding generations, except perhaps by those with an interest in martial arts fiction. The sweeping nature of its heterodox claims may have also impacted its popularity. For more on this work and its reception see The Sword or the Needle: The Female Knight Errant (Xia) in Traditional Chinese Narrative by Roland Altenburger (Peter Lang Publishing, 2009).

Perhaps the lasting contribution of this work was its discussion of gender. Altenburger notes that the novel seems to totally uproot traditional hierarchies and this includes extolling the martial virtues and potential of Yin, or female energies, while at the same time “deflating” male figures and archetypes. In previous novels female swordsman succeeded only by becoming, in effect, “honorary men.” Yet that is not the strategy of the heaven-sent protagonist of Nuxain Waishi. This fictionalized version of Tang represents the Yin energies of the moon and she embraces them to use them to their full advantage.

This choice raises a pressing question. How can a smaller weaker female body triumph in the intensely physical realm of the knight-errant, where one is expected to meet you enemy not just through strategy (long seen as the strong suit of female warriors) but also through force of arms? For Lu the answer was clear. Tang was renown as a female Daoist adept, so the answer must be magic.

While somewhat jarring to modern readers I think this move makes a lot of sense. The Yin forces of corruption and chaos had always been feared on the battlefield. As late as the end of the 19th century military leaders in China had attempted to co-opt Yin magic and turn it to their own ends. It was entirely in keeping with character for Lu to endow his heroine with these same abilities.

Nuxain Waishi may have had a limited readership, but many of its themes went on to influence other, more important novels. Altenburger notes a number of intertextual dependencies between it and Xianxia Wu Huajian (Five Flower Swords of the Immortal Knights, 1900). This novel, published under the pseudonym “The Shanghai Sword Freak” by Sun Jiazhen, had a much deeper impact on the development of the modern martial arts novel.

Sales of the initial publication were quite good. It was so popular that in the early Republic era many authors wrote unauthorized “sequels” hoping to cash in on its success. In fact, so many people were profiting from the work that its real author actually decided to get in on the act and write a sequel of his own which he had never originally intended to produce. In this way Sun’s initial story spawned an entire group of novels. This body of literature, all of which was connected to the memory of Tang Saier, helped to popularize the idea of the female knight errant and set the stage for its the subsequent explosion in the popular consciousness.

Like other authors before him, Sun was forced to ask where exactly a female martial artist would receive her skill or strength from. Sadly none of these story tellers were actually connected with the real martial arts, so once again magic seemed like a plausible answer. But this magic had to be different from that employed in the 1711 novel.

In the earlier story Tang was reimagined as a heavily emissary. She was an embodied immortal sent to protect the legitimate Ming emperor from his corrupt uncle. But in Flower Sword the plot is more complicated. A group of immortals are sent to convey their skills, but they must recruit human disciples who are responsible for fighting the battles of this world. Ultimately the story develops a gender balanced cast of characters. But how do these fully-human females survive in their new calling?

This time it is Daoist alchemy that is specifically invoked. Human male martial artists recruited by the brotherhood need no physical augmentation to learn the superhuman techniques of the immortals. Female recruits, however, are given a pill made through alchemical processes. It strengthens them and hardens their bodies, as well as replacing their bones with light. Still, the process leaves them in essence female. They are not so much endowed with Yang properties as made capable of defending themselves through their Yin powers. They must also master their boxing skills the old fashioned way, through practice.

This sort of flashy external alchemy allows for exciting plots and tense confrontations between good and evil. Yet at the same time that this is coming out Sun Lutang is starting to publish his own martial philosophy, now available to the middle class reading public. In these works he too claims that a combination of martial arts and Daoist practices could renew health and promote longevity. However, for Sun the alchemical furnace that powers this transformation is the internal one. It goes without saying that his ideas were the more reasonable ones, but ultimately it was the thriller wuxia novels that sold more copies.

Conclusion

Tolkien’s initial warnings should be carefully considered. It is a difficult and dangerous thing to take a living story and try to understand where it came from. Difficult because in the process of writing, information is not just conveyed, it is twisted, molded and recombined in irrevocable ways. Once you have made the ox into a soup there is no way to reconstruct the draft animal, let alone to understand its place in an early agrarian society. The exercise is dangerous as stories are written for a reason, and in breaking them down into a series of interconnected parts we are prone to miss the emergent properties of the system as a whole. Those were, after all, what attracted most readers or listeners in the first place.

Still, we have learned some important facts about the evolution of Chinese popular culture. It is certainly true that the motif of the female martial artists exploded in popularity in the early Republic period. We cannot analyze and understand the Wing Chun creation myth, or many other modern hand combat legends, if we divorce them from this setting.

Yet we have also discovered that this motif has much deeper roots in Chinese literature and culture. It is possible to find stories of important female warriors in practically every period of Chinese history. For the sake of brevity I restricted the current essay to an examination of a single figure from the Ming dynasty, but this exercise could be repeated any number of times.

Tang Saier is interesting to us for a number of reasons. Obviously the story of a female religious adept turned warrior has many echoes in the folklore of the southern Chinese martial arts. Her evasion of the Yongle Emperor’s attempts to reassert control over the temples and arrest the nuns even prefigures the development of literary figures like Ng Moy in important ways.

Yet what is really remarkable is the relative ease with which we can trace the development of stories based on her life and their subsequent incorporation into modern literature. It may not be possible to identify all of the source material behind the Wing Chun creation myth, but stories like this one certainly helped to give it flavor.

Of course one central question remains unanswered. We have now seen how the idea of the female knight-errant exploded in Republic era popular literature, but why did this trend emerge in the first place? And what relationship, if any, did it have to the transformation of China’s traditional hand combat systems? We will pursue these questions in a future post.