Antique hudiedao or “butterfly swords.” These weapons are commonly seen in a number of styles of southern Kung Fu including Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar and Wing Chun. Source: Author’s personal collection.

In January of 2013 I posted an essay titled “A Social and Visual History of the Hudiedao (Butterfly Sword) in the Southern Chinese Martial Arts.” As a student of Wing Chun I have always been fascinated by these weapons, and as a researcher in the field of martial arts studies I have been equally curious as to what they reveal about life in Southern China during the 19th and 20th centuries. I was both surprised and gratified to discover just how many of you share my enthusiasm for these questions. That post has become one of the most frequently visited articles here at Kung Fu Tea.

While revisiting that document as part of my current research, it occurred to me that it was time to offer an updated and revised version. Since writing that piece I have encountered a number of other important sources that have added to, and modified, our understanding of these iconic weapons. Some of those discoveries have been discussed in various places on the blog. In truth, our current body of knowledge is too large to be contained in a single post. Nevertheless, I felt like Kung Fu Tea’s readership deserved a more up to date resource.

To maximize continuity I have kept the original text of the article where possible, deleted sections or made edits where necessary and added new discussions, images and topics where space would permit. A notice has also been added to the top of the original post directing readers to the newly updated and expanded version.

I would like to extend a special note of thanks to Swords and Antique Weapons for allowing me to use a number of wonderful photographs of hudiedao that have passed through their collection over the years. It would have been very difficult to present anything approaching a complete survey of the subject without their assistance. Also, Peter Dekker has generously shared the fruits of his own extensive research on Chinese swords and weapons. His insights have been most helpful.

Introduction: What do we really know about butterfly swords?

No weapon is more closely linked to the martial heritage of southern China than the hudiedao (Cantonese: wu dip do), commonly referred to in English as “butterfly swords.” In the hands of Wing Chun practitioners such as Bruce Lee and Ip Man, these blades became both a symbol of martial attainment and a source of regional pride for a generation of young martial artists.

Nor are these blades restricted to a single style. Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar, Lau Gar and White Crane (among numerous others) all have lineages that employ this weapon. Prior to the modern era these swords were also a standard issue item in the region’s many gentry led militias and private security forces. Even ocean going merchant vessels would carry up to two dozen sets of these swords as part of their standard compliment of sailing gear. The hudiedao are worthy of careful study precisely because they have functioned as a widespread and distinctive cultural marker of the southern Chinese martial arts.

This is not to say that hudiedaos are not occasionally seen in other places. They have been carried across China by the adventurous people of Guangdong and Fujian. By the late 19th century they were making regular appearances in diaspora communities in Singapore and even California. Today they can be found in training halls around the world.

Of course there are a number of other Chinese fighting traditions which have focused on paired swords, daggers or maces that are very reminiscent of the butterfly swords of southern China. Still, there are distinctive elements of this regional tradition that make it both easily identifiable and interesting to study.

The following post offers a brief history of the hudiedao. In attempting to reconstruct the origin and uses of this weapon I employ three types of data. First, I rely on dated photographs and engravings with a clear provenance. These images are important because they provide evidence as to what different weapons looked like and who carried them.

Secondly, I discuss a number of period (1820s-1880s) English language accounts to help socially situate these weapons. These have been largely neglected by martial artists, yet they provide some of the earliest references that we have to the widespread use of butterfly swords or, as they are always called in the period literature, “double swords.” While the authors of these accounts are sometimes hostile observers (e.g., British military officers), they often supply surprisingly detailed discussions of the swords, their methods of use and carry, and the wider social and military setting that they appeared in. These first-hand accounts are gold mines of information for military historians.

Lastly, we will look at a number of surviving examples of hudiedao from private collections. It is hard to understand what these weapons were capable of (and hence the purpose of the various double sword fighting forms found in the southern Chinese martial arts) without actually handling them.

Modern martial artists expect both too much and too little from the hudiedao. With a few exceptions, the modern reproductions of butterfly swords are either beautifully made a-historical “artifacts,” high tech simulacra of a type of weapon that never actually existed in 19th century China, or cheaply made copies of practice gear that was never meant to be a “weapon” in the first place. This second class of “weapon” sets the bar much too low. Yet it is also nearly impossible for any flesh and blood sword to live up to the mythology and hype that surrounds butterfly swords, especially in Wing Chun circles. As these swords appear with ever greater frequency on TV programs and within video games, that mythology grows only more entrenched.

Unfortunately antique butterfly swords are hard to find and highly sought after by martial artists and collectors. They are usually too expensive for most southern style kung fu students to actually study. I hope that a detailed historical discussion of these swords may help to fill in some of these gaps. While there is no substitute for holding a weapon in one’s hands, a good overview might give us a much better idea of what sort of weapon we are attempting to emulate. It will also open valuable insights into the milieu from which these blades emerged.

This last point is an important one. Rarely do students of Chinese martial studies inquire about the social status or meaning of weapons. This is a serious oversight. As we have seen in our previous discussions of Republic era dadaos and military kukris, the social evolution of these weapons is often the most interesting and illuminating aspect of their story. Who used the hudiedao? How were they employed in combat? When were they first created, and what did they mean to the martial artists of southern China? Lastly, what does their spread tell us about the place of the Chinese martial arts in an increasingly globalized world?

The short answer to these questions is that butterfly swords were popular with civilian martial artists in the 19th century. While never an official “regulation weapon” within the imperial Qing military they may have been a local adaptation of the “Green Standard Army Rolling Blanket Double Sabers” seen in official manuals outlining the weapons of both the Ming and Qing armies. Based on his translations of 皇朝禮器圖式, Peter Dekker notes that these blades (shaped like small military sabers) had the following dimensions:

The left and right opposites are each 2 chi 1 cun and 1 fen long. [Approx. 73 cm]. The blades are 1 cun 6 fen long. [Approx. 56 cm]. Width is 1 cun [Approx 3.5 cm].

The Rolling Blanket Saber of the Green Standard Army as discussed in the 皇朝禮器圖式. 1766 woodblock print, based on a 1759 manuscript. Subsequent editions from 1801 and 1899 reproduced basically identical images. Source: Peter Dekker.

While dressed to look like standard issue sabers, these double blades were actually comparably sized to many of the “war era” hudiedao that can be found in collections today. Thus there may be more of a military rational for the existence of such weapons than was previously thought. While the vast majority of butterfly swords were owned or used by civilians, this might also suggest an explanation of why a few pairs have been found with military markings. It is hypothetically possible that at least some of these swords were seen as a locally produced variant of a known military weapon.

While exciting, we must be careful not to over-interpret this discovery. When discussing the martial arts were are, by in large, referencing a civilian realm that, while related to military training, remained socially distinct from it. To be a “martial artist” in 19th century China was to be a member of one or more other overlapping social groups. For instance, many martial artists were one or more of the following: a professional soldier, a bandit or pirate, a member of a militia or clan defense society, a pharmacist or an entertainer.

As we review the historical accounts and pictures below, we will see butterfly swords employed by members of each of these categories. That is precisely why this exercise is important. Hudiedao are a basic technology that help to tie the southern martial arts together. If we can demystify the development and spread of this one technology, we will make some progress toward understanding the background milieu that gave rise to the various schools of hand combat that we have today.

A set of mid. 19th century hudiedao. These swords are 63 cm long have strong blades with a thick triangular spine (14 mm at the forte). They were capable of cutting but clearly optimized for stabbing. The edge itself has a convex grind on one side, and a flat grind where it sits against the other sword when sheathed. The blades also feature steel D-guards and rosewood handles decorated with carved phoenixes. This image was provided courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com, a reliable source for authentic antique Chinese arms.

Hudiedao: Understanding the basic history of the butterfly sword.

The monks of the Shaolin Temple have left an indelible mark on the martial arts of Guangdong and Fujian. This mark is none the less permanent given the fact that the majority of Chinese martial studies scholars have concluded that the “Southern Shaolin Temple” was a myth. Still, myths reflect important social values. Shaolin (as a symbol) has touched many aspects of the southern Chinese martial arts, including its weapons.

In Wing Chun Schools today, it is usually assumed that the art’s pole form came from Jee Shim (the former abbot of the destroyed Shaolin sanctuary), and that the swords must have came from the Red Boat Opera or possibly Ng Moy (a nun and another survivor of temple). A rich body of lore linking the hudiedao to Shaolin has grown over the years. These myths often start out by apologizing for the fact that these monks are carrying weapons at all, as this is a clear (and very serious) breach of monastic law.

It is frequently asserted that our monks needed protection on the road from highwaymen, especially when they were carrying payments of alms. Some assert that butterfly swords were the only bladed weapons that the monks were allowed to carry because they were not as deadly as a regular dao. The tips could be left blunt and the bottom half of the blade was often unsharpened. Still, there are a number of problems with this story.

These blunt tips and unsharpened blades seem to actually be more of an apology for the low quality, oddly designed, practice swords that started to appear in the 1970s than an actual memory of any real weapons.

The first probable references to the hudiedao (or butterfly swords) that I have been able to find date to the 1820s. Various internet discussions, some quite good and worth checking out, as well as Jeffery D. Modell’s article “History & Design of Butterfly Swords” (Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine, April 2010, pp. 56-65) usually suggest a later date of popularization. Modell concludes that the traditional butterfly sword is a product of the “late 19th century” while other credible sources generally point to the 1850s or 1860s. The general consensus seems to be that while a few examples may have existed earlier, this weapon did not really gain prominence until the middle or end of the 19th century.

This opinion was formed mostly through the first hand examination of antique blades. And it is correct so far as it goes. Most of the existing antique blades do seem to date from the end of the 19th century or even the first few decades of the 20th. Further, this would fit with our understanding of the late 19th century being a time of martial innovations, when much of the foundation for the modern Chinese hand combat systems was being set in place.

Recently uncovered textual evidence would seem to indicate that we may need to roll these dates back by a generation or more. As we will see below, already in the 1820s western merchants and British military officers in Guangzhou were observing these, or very similar weapons, in the local environment. They were even buying examples that are brought back to Europe and America where they enter important early private collections.

The movement of both goods and people was highly restricted in the “Old China Trade” system. Westerners were confined to one district of the Guangzhou and they could only enter the city for a few months of the year. The fact that multiple individuals were independently collecting examples of hudiedao, even under such tight restrictions, would seem to indicate that these weapons (or something very similar to them) must have already been fairly common in the 1820s.

Accounts of these unique blades become more frequent and more detailed in the 1830s and 1840s. Eventually engravings were published showing a wide variety of arms (often destined for private collections or the “cabinets” of wealthy western individuals), and then from the 1850s onward a number of important photographs were produced. The Hudiedao started to appear in images on both sides of the pacific, and it is clear that the weapon had a well-established place among gangsters and criminals in both San Francisco and New York.

But what exactly is a hudiedao? What sorts of defining characteristics binds these weapons together and separate them from other various paired weapons that are seen in the Chinese martial arts from time to time?

Readers should be aware that not every “double sword” is a hudiedao. This is a pair of jians dating to the late 19th century. Notice that this style of swords is quite distinct on a number of levels. Rather than being fit into a simple leather scabbard with a single opening, these swords each rest in their own specially carved compartment. As a result the blades are not flat-ground on one side (as is the case with true hudiedao) and instead have the normal diamond shaped profile. These sorts of double swords are more common in the northern Chinese martial arts and also became popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They are usually called Shuang Jain (or Shuang Dao for a single edged blade), literally “double swords.

Unfortunately, this is exactly the same term that many English language observers used when they encountered Hudiedao in Guangzhou and Hong Kong in the middle of the 19th century. Further complicating the matter, some southern fighting forms call for the use of two normal sabers to be used simultaneously, one in each hand. Interpreting 19th century accounts of “double swords” requires a certain amount of guess work. Photos courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

Note the construction of the scabbard. Period sources seem to imply that swords were classified in large part by their scabbard construction (how many openings the blades shared), and not just by the blades shape or function. these images were provided courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons,com.

The term “hudiedao,” or “butterfly sword,” never appears in any of the 19th century English language accounts that I have examined. Invariably these records and illustrations refer instead to “double swords.” A number of them go to lengths to point out that this is a weapon unique to China. Its defining characteristic seems to be that the two blades are fitted together in such a way that they can be placed in a shared opening to one sheath. Some accounts (but not all) go on to describe heavy D guards and the general profile of the blade. I used these more detailed accounts (from the 1830s) and engravings and photos (from the 1840s and 1850s) to try and interpret some of the earlier and briefer descriptions (from the 1820s).

Some of these collectors, Dunn in particular, were quite interested in Chinese culture and had knowledgeable native agents helping them to acquire and catalog their collections. It is thus very interesting that these European observers, almost without exception, referred to these weapons as “double swords” rather than “butterfly swords.” Not to put too fine a point on it, but some western observers seemed to revel in pointing out the contradictory or ridiculous in Chinese culture, and if any of them had heard this name it would have recorded, if only for the ridicule and edification of future generations.

I looked at a couple of period dictionaries (relevant to southern China) that included military terms. None of them mentioned the word “Hudiedao,” though they generally did include a word for double swords (雙股劍: “shwang koo keem,” or in modern Pinyin, “shuang goo gim.” See Medhurst, English and Chinese Dictionary 1848; Morrison, Dictionary of the Chinese Language, 1819.)

Multiple important early Chinese novels, including the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin (All Men are Brothers) include protagonists who use these weapons, so for that reason alone this would be a commonly understood term. Even individuals who were not martial artists would have known about these literary characters and their weapons. In fact, the literary legacy of those two novels could very well explain how these blades have managed to capture the imagination of so many martial artists up through the 21st century.

In modern martial arts parlance, “double swords” (shuang jian or shuang dao) refer to two medium or full size jians (or daos) that are fitted into a single scabbard. These weapons also became increasingly popular in the late 19th century and are still used in a variety of styles. It is possible that they are a different regional expression of the same basic impulse that led to the massive popularization of hudiedao in the south, but they are a fairly different weapon.

The real complicating factor here is that neither type of weapons (shuang dao vs. hudiedao) was ever adopted or issued by the Imperial military, so strictly speaking, neither of them have a proper or “official name.” (Again, while similar in size and function, the “Rolling Blanket Double Sabers” clearly followed the forging and aesthetic guidelines seen in all other military sabers and were categorized accordingly.) When looking at these largely civilian traditions, we are left with a wide variety of, often poetic, ever evolving terms favored by different martial arts styles. Occasionally it is unclear whether these style names are actually meant to refer to the weapons themselves, or the routines that they are employed in.

The evolution of the popular names of these weapons seems almost calculated to cause confusion. For our present purposes I will be referring to any medium length, single edged, pair of blades fitted into a shared scabbard, as “hudiedaos.” Readers should be aware of the existence of a related class of weapon which resembles a longer, single, hudiedao. These were meant to be used in conjunction with a rattan shield. They are only included in my discussion only if they exhibit the heavy D-guard and quillion that is often seen on other butterfly swords.

Hudiedao were made by a large number of local smiths and they exhibit a great variability in form and intended function. Some of these swords are fitted with heavy brass D-guards (very similar to a European hanger or cutlass), but in other cases the guard is made of steel. On some examples the D-guard is replaced with the more common Chinese S-guard. And in a small minority of cases no guard was used at all.

Another set of Hudiedao exhibiting different styling. An S-guard is used on these swords, which are more common on Chinese weapons. These knives are 45 cm long and are both shorter and lighter than some of the preceding examples. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

The sorts of blades seen on hudiedao from southern China can also vary immensely. Two types are most commonly encountered on 19thcentury weapons. Some are long and narrow with a thick triangular cross section. These blades superficially resemble shortened European rapiers and are clearly designed with stabbing in mind. Other blades are wider and heavier, and exhibit a sturdy hatchet point. While still capable of stabbing through heavy clothing or leather, these knives can also chop and slice.

Most hudiedao from the 19th century seem to be medium sized weapons, ranging from 50-60 cm (20-24 inches) in length. It is obvious that arms of this size were not meant to be carried in a concealed manner. To the extent that these weapons were issued to mercenaries (or “braves”), local militia units or civilian guards, there would be no point in concealing them at all. Instead, one would hope that they would be rather conspicuous, like the gun on the hip of a police officer.

These hudiedaos have thick brass grips, a wider blade better suited for chopping and a strong hatchet point. Their total length is just over 60 cm. This was the most commonly produced type of “butterfly sword” during the middle of the 19th century. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

While these two blade types are the most common (making up about 70% of the swords that I have encountered), other shapes are also seen. Some hudiedao exhibit the “coffin” shaped blades of traditional southern Chinese fighting knives. These specimens are very interesting and often lack any sort of hand guard at all, yet they are large enough that they could not easily be used like their smaller cousins.

One also encounters blades that are shaped like half-sized versions of the “ox-tail” dao. This style of sword was very popular among civilian martial artists in the 19th century. Occasionally blades in this configuration also show elaborate decorations that are not often evident on other types of hudiedao.

This set of Butterfly Swords has a number of unusual features. Perhaps the most striking are its wood (rather than leather) scabbard and high degree on ornamentation. These were almost certainly collected in French Indo-China and likely date to 1900-1930. They are 49 cm in length and show a pronounced point. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

These unusual hudiedao feature handles and blades that are loosely based on traditional Chinese fighting knives. In this case the blade has been made both longer and wider. Fighting knives do not commonly have hand guards, which are also missing from this example. I have seen a couple of sets of knives in this configuration, though they seem to be quite rare. These knives are 49 cm long and 65 mm wide at the broadest point. Possibly early 20th century. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

These hudiedao are more reminiscent of the blades favored by modern Wing Chun students. They show considerable wear and date to either the middle or end of the 19th century. The tips of the blades are missing and may have been broken or rounded off through repeated sharpening. I suspect that when these swords were new they had a more hatchet shaped tip. Their total length is 49 cm. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

Lastly there are shorter, thicker blades, designed with cutting and hacking in mind. These more closely resemble the type favored by Wushu performers and modern martial artists. Some of these weapons could be carried in a concealed manner, yet they are also better balanced and have a stronger stabbing point than most of the inexpensive replicas being made today. It is also interesting to note that these shorter, more modern looking knives, can be quite uncommon compared to the other blade types listed above.

I am hesitant to assign names or labels to these different sorts of blades. That may seem counter-intuitive, but the very existence of “labels” implies a degree of order and standardization that may not have actually existed when these swords were made. 19th century western observers simply referred to everything that they saw as a “double sword” and chances are good that their Chinese agents did the same. Given that most of these weapons were probably made in small shops and to the exact specifications of the individuals who commissioned them the idea of different “types” of hudiedao seems a little misleading.

What defined a “double sword” to both 19th century Chinese and western observers in Guangdong, was actually how they were fitted and carried in the scabbard. These scabbards were almost always leather, and they did not separate the blades into two different channels or compartments (something that is occasionally seen in northern double weapons). Beyond that, a wide variety of blade configurations, hand guards and levels of ornamentation could be used. I am still unclear when the term “hudiedao” came into common use, or how so many independent observers and careful collectors could have missed it.

This engraving, published in 1801, is typical of the challenges faced when using cross-cultural sources in an attempt to reconstruct Chinese martial history. The image is plate number 20 from Major George Henry Mason’s popular 1801 publication Punishments of China (St James: W. Bulmer and Co.). Mason was in Guangzou (recovering from an illness) in 1789-1790. Given his experience in China, and interests in day to day life, he should have been a keen social observer. So how reliable are his prints? Does this image really show a soldier holding a set of “Rolling Blanket Double Sabers”, or something like them?

It is impossible to know what Mason actually saw or what to make of a print like this. Mason’s engravings were all based on watercolor paintings that he purchased from a Cantonese artist in Guangzhou named Pu Qua (Timothy Brook, Jérôme Bourgon, Gregory Blue. Death by a Thousand Cuts. Harvard University Press. 2008. P. 171). So what we really have here is an impressionistic engraving based off of a quickly sketched water color. While this image clearly suggests that some members of the local Yamen were using two medium sized swords, it is difficult to hazard a guess as to what the exact details of these weapons were. I attempt to avoid this type of problem by relying on first-hand accounts and more detailed (often photographic) images.

The First Written Accounts: Chinese “double swords” in Guangzhou in the 1820s-1830s.

The first English language written account of what is most likely a hudiedao that I have been able to find is a small note in the appendix of the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society for the year 1827. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Joseph Doyle had evidently acquired an extensive collection of oriental arms that he wished to donate to the society. In an era before public museums, building private collections, or “cabinets,” was a popular pastime for members of a certain social class.

The expansion of the British Empire into Asia vastly broadened the scope of what could be collected. In fact, many critical artistic and philosophical ideas first entered Europe through the private collections of gentlemen like Charles Joseph Doyle. Deep in the inventory list of his “cabinet of oriental arms” we find a single tantalizing reference to “A Chinese Double Sword.”

I have not been able to locate much information on Col. Doyle’s career so I cannot yet make a guess as to when he collected this example. Still, if the donation was made in 1825, the swords cannot have been acquired any later than the early 1820s. (Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 1. London: Royal Asiatic Society. 1827. “A Chinese double Sword. Donated on Nov. 5, 1825.” P. 636)

If Doyle’s entry in the records of the Royal Asiatic Society was terse, another prominent collector from the 1820 was more effusive. Nathan Dunn is an important figure in America’s growing understanding of China. He was involved in the “Old China Trade” and imported teas, silks and other goods from Guangdong to the US. Eventually he became very wealthy and strove to create a more sympathetic understanding of China and its people in the west.

For a successful merchant, his story begins somewhat inauspiciously. Historical records show that in 1816 Nathan Dunn was disowned (excommunicated) by the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers) for bankruptcy. While socially devastating, this bankruptcy may have been the best thing that ever happened to Dunn. In 1818 he left for China on a risky trading mission in an attempt to rebuild his fortune. He succeeded in that task many times over.

Unlike most western merchants Dunn found the Chinese to be very intelligent and worthy of close study and contemplation. He objected strenuously to the selling of opium (an artifact of his prior Quaker faith) and made valuable friendships and alliances with individuals from all levels of Chinese society. Appreciating his open outlook these individuals helped Dunn to amass the largest collection of Chinese artifacts in the hands of any one individual. In fact, the Chinese helped Dunn to acquire a collection many times larger than the entire cabinets of both the British East India Company and the British Government, which had been trying to build a vast display of its own for years.

Dunn’s collection was also quite interesting for its genuine breadth. It included both great works of art and everyday objects. It paid attention to issues of business, culture, horticulture and philosophy. Dunn made a point of studying the lives of individuals from different social and economic classes, and he paid attention to the lives and material artifacts of women. Finally, like any good 19th century gentleman living abroad, he collected arms.

Dunn’s collection went on display in Philadelphia in the 1838’s. When it opened to the public he had an extensive catalog printed (poetically titled 10,000 Chinese Things), that included in-depth discussions of many of the displays. This sort of contextual data is quite valuable. It is interesting to not only see double swords mentioned multiple times in Dunn’s collection, but to look at the other weapons that were also employed in the 1820s when these swords were actually being bought in Guangdong.

“The warrior is armed with a rude matchlock, the only kind of fire-arms known among the Chinese. There is hung up on the wall a shield, constructed of rattan turned spirally round a center, very similar in shape and appearance to our basket lids. Besides the matchlock and shield, a variety of weapons offensive and defensive, are in use in China; such as helmets, bows and arrows, cross-bows, spears, javelins, pikes, halberds, double and single swords, daggers, maces, a species of quilted armour of cloth studded with metal buttons, &c.” pp. 32-33.

“Besides these large articles, there are, in the case we are describing, an air-gun wooden barrel; a duck-gun with matchlock; a curious double sword, capable of being used as one, and having but one sheath; specimens of Chinese Bullets, shot powder, powder –horns, and match ropes…..” p. 42

“444. Pair of Swords, to be used by both hands but having one sheath. The object of which is to hamstring the enemy.” P. 51

“In addition to the spears upon the wall, there are two bows; one strung, and the other unstrung; two pair of double swords; one pair with a tortoise shell, and the other a leather sheath; besides several other swords and caps, and a jinjall, or a heavy gun on a pivot, which has three movable chambers, in which the powder and ball are put, and which serve to replace each other as often as the gun is discharged.” P. 93.

Enoch Cobb Wines. A Peep at China in Mr. Dunn’s Chinese Collection. Philadelphia: Printed for Nathan Dunn. 1839.

I found it interesting that Dunn would associate the double sword with “hamstringing” (the intentional cutting of the Achilles tendon) an opponent. In his 1801 volume on crime and punishment George Henry Mason included an illustration of a prisoner being “hamstrung” with a short, straight bladed knife. This was said to be a punishment for attempting to escape prison or exile. He noted that there was some controversy as to whether this punishment was still in use or if legal reformers in China had succeeded in doing away with it. It is possible that Dunn’s description (or more likely, that of his Chinese agent) on page 51 is a memory of the “judicial” use of the hudiedao by officers of the state against socially deviant aspects of society.

It is hard to overstate the importance of Dunn’s “Museum” in shaping China’s image in the popular imagination. As such, descriptions of his ethnographic objects reached the public through many outlets. One of these was the writings of W. W. Wood. Wood was a friend and collaborator of Dunn’s while in Canton. In fact, Wood was actually responsible for assembling most of the natural history section of the “China Museum.” Still, his writings touched on other aspects of the collecting enterprise as well.

CHINESE ARMS.

A great variety of weapons, offensive and defensive, are in use in China; such as matchlocks, bows and arrows, cross-bows, spears, javelins, pikes, halberds, double and single swords, daggers, maces, &c. Shields and armor of various kinds, serve as protection against the weapons of their adversaries. The artillery is very incomplete, owing to the bad mountings of the cannon, and efficient execution is out of the question, from the ignorance of the people in gunnery. Many of the implements of war are calculated for inflicting very cruel wounds, especially some kinds of spears and barbed arrows, the extraction of which is extremely difficult, and the injuries caused by them dreadful. A kind of sword, composed of an iron bar, about eighteen inches long, and an inch and a half thick, or two inches in circumference, is used to break the limbs of their adversaries, by repeated and violent blows.

The double swords are very short, not longer in the blade than a large dagger, the inside surfaces are ground very flat, so that when placed in contact, they lie close to each other, and go into a single scabbard. The blades are very wide at the base, and decrease very much towards the point. Being ground very sharp, and having great weight, the wounds given by them are severe. I am informed, that the principal object in using them, is to hamstring the enemy, and thus entirely disable him.

Most of the arms made in canton, are exceedingly rude and unfinished in comparison with our own, In the sword-making art they are better than in other departments, but the metal is generally of inferior quality, and the form of these weapons bad; the mountings are handsome, but there is little or no guard for the protection of the hand.

W. W. Wood. 1830. Sketches of China: with Illustrations from Original Drawings. Philadelphia: Carey & Lead. pp. 162-163

Woods descriptions of the hudieado are important on a number of counts. To begin with, they prove that European collectors had started to acquire these specimens by the 1820s. Further, the swords that he describes are relatively broad and short, similar to the weapons favored by many modern Wing Chun students. Lastly, his contextualization of these blades is invaluable.

These are the earliest references to “double swords” in southern China that I have been able to locate. Already by the 1820s these weapons were seen as something uniquely Chinese, hence it is not surprising that they would find their way into the collections and cabinets of early merchants and military officers.

Still, the 1820s was a time of relatively peaceful relations between China and the West. Tensions built throughout the 1830s and boiled over into open conflict in the 1840s. As one might expect, this deterioration in diplomatic relations led to increased interest in military matters on the part of many western observers. Numerous detailed descriptions of “double swords” emerge out of this period. It is also when the first engravings to actually depict these weapons in a detailed way were commissioned and executed.

Karl Friedrich A. Gutzlaff (English: Charles Gutzlaff; Chinese: Guō Shìlì) was a German protestant missionary in south-eastern China. He was active in the area in the 1830s and 1840s and is notable for his work on multiple biblical translations. He was the first protestant missionary to dress in Chinese style and was generally more in favor of enculturation than most of his brethren. He was also a close observer of the Opium Wars and served as a member of a British diplomatic mission in 1840.

One of his many literary goals was to produce a reliable and up to date geography of China. Volume II of this work spends some time talking about the Chinese military situation in Guangdong. While discussing the leadership structure of the Imperial military we find the following note:

(In a discussion of the “Chamber for the superintendent of stores and the examination of military candidates.):

“Chinese bows are famous for carrying to a great distance; their match-locks are wretched fire-arms; and upon their cannon they have not yet improved, since they were taught by the Europeans. Swords, spears, halberts, and partisans, are likewise in use in the army. Two swords in one scabbard, which enable the warrior to fight with the left and right hands, are given to various divisions. They carry rattan shields, made of wicker work, and in several detachments they receive armour to protect their whole body. The officers, in the day of battle, are always thus accoutered. Of their military engines we can say very little, they having, during a long peace, fallen into disuse.” P. 446.

Karl Friedrich A. Gützlaff. China opened; or, A display of the topography, history… etc. of the Chinese Empire. London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1838.

This is an interesting passage for a variety of reasons. It seems to very strongly suggest that the Green Standard Army in Guangdong was using large numbers of either Rolling Blanket Double Sabers or hudiedao in the 1830s, or at least stockpiling them. Occasionally I hear references to hudiedao being found that have official “reign marks” on them, or property marks of the Chinese military. Accounts such as this one might explain their existence.

The conventional wisdom (as we will see below) is that the hudiedao were never a “regulation” weapon and were issued only to civilian “braves” and gentry led militia units which were recruited by the governor of Guangdong in his various clashes with the British. Still, this note falls right in the middle of an extensive discussion of the command structure of the Imperial military. Who these various divisions were, and what relationship they had with militia troops, is an interesting question for further research.

This short saber might be thought of as an example of a single “hudiedao” given its aesthetic styling. It was never issued with a companion and has a fully round handle meaning that it cannot be slid into a scabbard besides another weapon. Short swords such as these were often issued to militia members who were armed with rattan shields. While not strictly the same as a hudiedao, its clear that this weapon is taking its styling cues from these other swords. The style of its leather scabbard, hilt and hand-guard are all identical to what was seen on period “butterfly swords.” This example measures 60 cm in length and would have been a good general short-range weapon. Photo courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

More specific descriptions of hudiedao and their use in the field started to pour in from reporters and government officers as the security situation along the Pearl River Delta disintegrated. The May 1840 edition of the Asiatic Journal includes the following notice:

“Governor Lin has enlisted about 3,000 recruits, who are being drilled daily near Canton in the military exercise of the bow, the spear and the double sword. The latter weapon is peculiar to China. Each soldier is armed with two short and straight swords, one in each hand, which being knocked against each other, produce a clangour [sic], which, it is thought, will midate [sic] the enemy.” P. 327

The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China and Australia. May-August, 1840. London: Wm. H. Allen and Co.

Such new recruits would clearly have been both “Braves” and members of the gentry led militia system. So this would seem to indicate that the hudiedao was a weapon favored by martial artists and citizen soldiers. This is also the first reference I have seen to soldiers beating their hudiedao together to make a clamor before charging into battle. While this tactic is usually noted with disdain by British observers, it is well worth noting that their own infantry often put on a similar display before commencing a bayonet charge.

Another set of hudiedao from the private collection of Gavin Nugent. These blades are some of the earliest seen in this post. They also show signs of significant period use. Note the complex profile of the blades and how the spine flattens out as it approaches the tip. This allows the weapon to have reach while not feeling “top heavy.” The owner notes that these are the most comfortable hudiedao that he has handled. The nicely executed brass tunkou (collar around the blade) are an interesting and rarely seen feature. Source: http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

Born in 1805 (1805-1878) J. Elliot Bingham served for 21 years in the Royal Navy. In the late 1830s he had the rank of First Lieutenant (he later retired as a Commander) and was assigned to the H. M. S. Modeste. Launched in 1837, this 18 Gun Sloop or corvette was crewed by 120 sailors and marines. It saw repeated combat along the Guangdong coast and the Pearl River between 1839 and 1841.

As a military man Commander Bingham was a close observer of Chinese weapons and he leaves us with what must be considered the very best account of the use of hudiedao by militia troops in the late 1830s.

“March the 21st, Lin was busy drilling 3,000 troops, a third portion of which was to consist of double-sworded men. These twin swords, when in scabbard, appear as one thick clumsy weapon, about two feet in length; the guard for the hand continuing straight, rather beyond the “fort” of the sword turns toward the point, forming a hook about two inches long. When in use, the thumb of each hand is passed under this hook, on which the sword hangs, until a twist of the wrist brings the grip within the grasp of the swordsman. Clashing and beating them together and cutting the air in every direction, accompanying the action with abuse, noisy shouts and hideous grimaces, these dread heroes advance, increasing their gesticulations and distortions of visage as they approach the enemy, when they expect the foe to become alarmed and fly before them. Lin had great faith in the power of these men.” P. 177-178.

J. Elliot Bingham. Narrative of the Expedition to China, from the Commencement of the Present Period. Volume 1. London: Henry Colburn Publisher. 1842.

Commander Bingham was not much impressed by the Chinese militia or their exotic weaponry. In truth, Lin led his forces into a situation where they were badly outgunned, and more importantly “out generaled,” by the seasoned and well led British Navy. Still, his brief account contains a treasure trove of information. To begin with, it confirms that the earlier accounts of “double swords” used by the militia in and around Guangzhou in the 1830s were in fact references to hudiedao.

Fredric Wakeman, in his important study Stranger at the Gate: Social Disorder in Southern China 1839-1861, cites intelligence reports sent to the British Foreign Office which claim that Lin had in fact raised a 3,000 man force to repel a foreign attach on Guangzhou. Apparently Lin distrusted the ability of the Green Standard Army to get the job done, and the Manchu Banner Army was so poorly disciplined and run that he actually considered it to be a greater threat to the peace and safety of the local countryside than the British.

He planned on defending the provincial capital with a two pronged strategy. First, he attempted to strengthen and update his coastal batteries. Secondly, he called up the gentry led militia (and a large number of mercenary braves) because these troops were considered more committed and reliable than the official army. Bingham was correct, Lin did put a lot of confidence in the militia.

The Foreign Office reported that Lin ordered every member of the militia to be armed with a spear, a rattan helmet, and a set of “double swords” (Wakeman 95). Other reports note that members of the militia were also drilled in archery and received a number of old heavy muskets from the government stores in Guangdong. Bingham’s observations can leave no doubt that the “double swords” that the Foreign Office noted were in fact hudiedao.

Local members of the gentry worked cooperatively out of specially built (or appropriated) Confucian “schools” to raise money, procure arms and supplies for their units, to organize communications systems, and even to create insurance programs. It seems likely that the hudiedao used by the militia would have been hurriedly produced in a number of small shops around the Pearl River Delta.

Much of this production likely happened in Foshan (the home of important parts of the Wing Chun, Choy Li Fut and Hung Gar movements). Foshan was a critical center of regional handicraft production, and it held the Imperial iron and steel monopoly (He Yimin. “Thrive and Decline:The Comparison of the Fate of “The Four Famous Towns” in Modern Times.” Academic Monthly. December 2008.) This made it a natural center for weapons production.

We know, for instance, that important cannon foundries were located in Foshan. The battle for control of these weapon producing resources was actually a major element of the “Opera Rebellion,” or “Red Turban Revolt,” that would rip through the area 15 years later. (See Wakeman’s account in Stranger at the Gate for the most detailed reconstruction of the actual fighting in and around Foshan.)

Given that this is where most of the craftsmen capable of making butterfly swords would have been located, it seems reasonable to assume that this was where a lot of the militia weaponry was actually produced. Further, the town’s centralized location on the nexus of multiple waterways, and its long history of involvement in regional trade, would have made it a natural place to distribute weapons from.

While all 3,000 troops may have been armed with hudiedao, it is very interesting that these weapons were the primary arms of about 1/3 of the militia. Presumably the rest of their comrades were armed with spears, bows and a small number of matchlocks.

Bingham also gives us the first clear description of the unique hilts of these double swords. He notes in an off-handed way that they have hand-guards. More interesting is the quillion that terminates in a hook that extends parallel to the blade for a few inches. This description closely matches the historic weapons that we currently possess.

This style of guard, while not seen on every hudiedo, is fairly common. It is also restricted to weapons from southern China. Given that this is not a traditional Chinese construction method, various guesses have been given as to how these guards developed and why they were adopted.

There is at least a superficial resemblance between these guards and the hilts of some western hangers and naval cutlasses of the period. It is possible that the D-guard was adopted and popularized as a result of increased contact with western arms in southern China. If so, it would make sense that western collectors in Guangzhou in the 1820s would be the first observers to become aware of the new weapon.

The actual use of the hooked quillion is also open to debate. Many modern martial artists claim that it is used to catch and trap an opponent’s blade. In another essay I have reviewed a martial arts training manual from the 1870s that shows local boxers attempting to do exactly this. However, as the British translator of that manual points out (and I am in total agreement with him), this cannot possibly work against a longer blade or a skilled and determined opponent. While this type of trapping is a commonly rehearsed “application” in Wing Chun circles, after years of fencing practice and full contact sparring, my own school has basically decided that it is too dangerous to attempt and rarely works in realistic situations.

Another theory that has been advanced is that the hook is basically symbolic. It is highly reminiscent of the ears on a “Sai,” a simple weapon that is seen in the martial arts of China, Japan and South East Asia. Arguments have been made that the sai got its unique shape by imitating tridents in Hindu and Buddhist art. Perhaps we should not look quite so hard for a “practical” function for everything that we see in martial culture (Donn F. Draeger. The Weapons and Fighting Arts of Indonesia. Tuttle Publishing. 2001. p. 33).

Bingham makes a different observation about the use of the quillion. He notes that it can be used to manipulate the knife when switching between a “reverse grip” and a standard fencing or “brush grip.” Of course the issue of “sword flipping” is tremendously controversial in some Wing Chun circles, so it is interesting to see a historical report of the practice in a military setting in the 1830s.

It is also worth noting that Commander Bingham was not the only Western observer to describe hudiedao training and to doubt its effectiveness.

Of swords the Chinese have an abundant variety. Some are single-handed swords, and there is one device by which two swords are carried in the same sheath and are used one in each hand. I have seen the two sword exercise performed, and can understand that, when opposed to any person not acquainted with the weapon, the Chinese swordsman would seem irresistible. But in spite of the two swords, which fly about the wielder’s head like the sails of a mill, and the agility with which the Chinese fencer leaps about and presents first one side and then the other to this antagonist, I cannot think but that any ordinary fencer would be able to keep himself out of reach, and also to get in his point, in spite of the whirling blades of the adversary.

J. G. Wood. 1876. The Uncivilized Races of All Men in All Countries. Vol. II. Hartford: the J. B. Burr Publishing Co. Chapter, CLIV China—continued. Warfare.—Chinese Swords. pp. 1434-1435. (Originally published in 1868.)

J. G. Wood, while responsible for few discoveries of his own, was one of the great promoters and popularizers of scientific knowledge in his generation. Most of his writings focused on natural history, but occasionally he ventured into the realm of ethnography. Like Dunn, Wood was a collector by nature. So its not hard to imagine him amassing a number of Chinese swords.

Yet where would he have seen these skills demonstrated? While Wood traveled to North America on a lecture tour, I am aware of no indication that he ever ventured as far as China. Of course, one did not have to go to Hong Kong or Shanghai to see a martial arts demonstration. Between 1848 and 1851 the crew of the Keying (a Chinese Junk) staged twice daily Kung Fu performances in London.

Stephen Davies, who is an expert of the voyages of the Keying, has hypothesized that by the time the ship reached London almost all of its original Chinese crew had already left and returned home. If this is true, the Keying would have had to recruit a replacement “crew” from London’s small Victorian era Chinese community. If his supposition is correct (and to be clear, I feel this still needs additional confirmation), by the middle of the 19th century the UK may have had its own population of indigenous martial artists, more than willing to perform their skills in public. J. G. Wood’s account suggests that the butterfly sword was a well established part of their repertoire.

A very nice set of mid. 19th century hudiedao. These pointed stabbing blades are 63 cm long, 40 mm wide at the base, and the spine in 14 mm across, giving the entire weapon a strong triangular profile. Image courtesy of http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

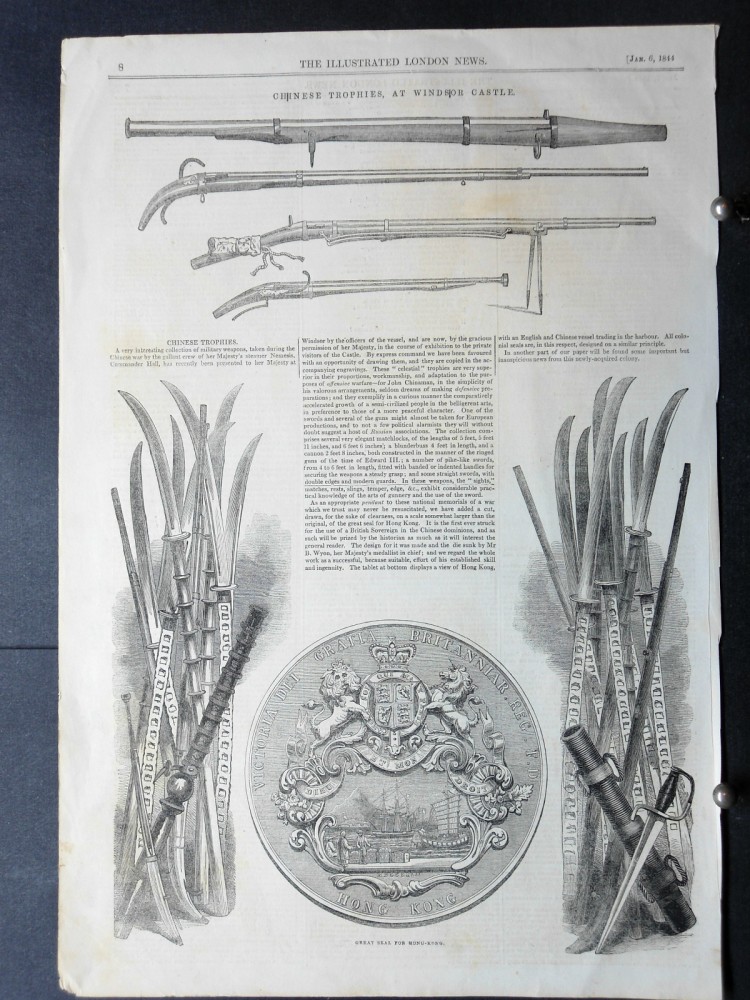

Early Images of the Hudiedao: Western Engravings of Chinese Arms.

It was rare to encounter collections of Chinese artifacts of any kind in the 1820s and 1830s. However, the situation changed dramatically after the First and Second Opium Wars. The expansion of trade that followed these conflicts, the opening of new treaty ports, and the creation and growth of Hong Kong all created new zones where Chinese citizens and westerners could meet to change goods and artifacts of material culture. Unfortunately these meetings were not always peaceful and a large number of Chinese weapons started to be brought back to Europe as trophies. Many of these arms subsequently found their way into works of art. As a quintessentially exotic Chinese weapon, “double swords” were featured in early engravings and photographs.

Our first example comes from an engraving of Chinese weapons captured by the Royal Navy and presented to Queen Victoria in 1844. The London Illustrated News published an interesting description of what they found. In addition to a somewhat archaic collection of firearms, the Navy recovered a large number of double handed choppers. These most closely resemble weapon that most martial artists today refer to as a “horse knife” (pu dao).

Featured prominently in the front of the engraving is something that looks quite familiar. The accompanying article describes this blade as having “two sharpened edges” and a “modern guard.” I have encountered a number of hudiedao with a false edge, but I do not think that I have found one that was actually sharpened. I suspect that the sword in this particular picture was of the single variety and originally intended for use with a wicker shield.

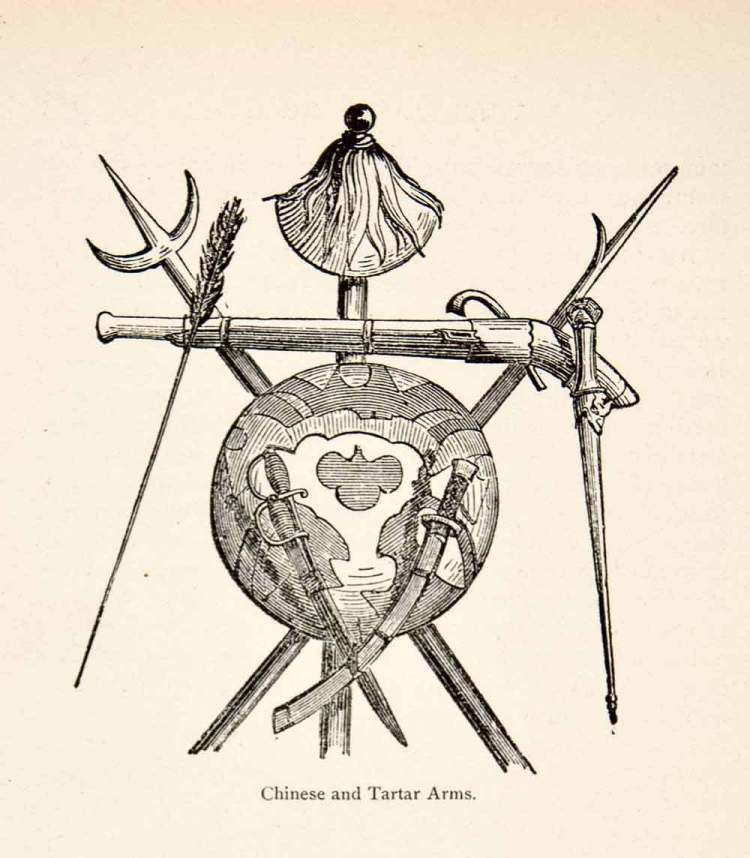

Another useful engraving of “Chinese and Tartar Arms” can be found in Evariste R. Huc’s Travels in Tartary, Thibet and China (London, 1852). Unlike some of the previous sources this one is not overly focused on military matters. Still, the publishers include a fascinating engraving of Chinese arms. The models for these were likely war trophies that were brought to the UK in the 1840s and 1850s. They may have even been items from Nathan Dunn’s (now deceased) vast collection which was auctioned at Sotheby in 1844 following a tour of London and then the countryside.

Featured prominently in the middle of the picture is a set of hudiedao. The engraving shows two swords with long narrow blades and D-guards resting in a single scabbard. It is very hard to judge size in this print as the artist let scale slide to serve the interests of symmetry, but it appears that the “double swords” are only slightly shorter than the regulation Qing dao that hangs with them.

“Chinese and Tartar Arms.” Published in Evariste R. Huc. Travels in Tartary, Thibet and China, 1844-5-6. Volume 1. P. 237. Office of the National Illustrated Library. London: 1852.

While it would appear that hudiedao had been in use in southern China since the 1820s, they make their first documented appearance on the West coast of America in the 1850s. The Bancroft Library at UC Berkley has an important collection of documents and images relating to the Chinese American experience. Better yet, many of their holdings have been digitized and are available on-line to the public.

Most of the Chinese individuals who settled in California (to work in both the railroads and mining camps) were from Fujian and Guangdong. They brought with them their local dialects, modes of social organization, tensions and propensity for community feuding and violence. They also brought with them a wide variety of weapons.

Newspaper accounts and illustrations from this side of the pacific actually provide us with some of our best studies of what we now think of as “martial arts” weapons. Of course, it is unlike that this is how they were actually viewed by immigrants in the 1850s. In that environment they were simply “weapons.”

The coasts of both Guangdong and Fujian province were literally covered in pirates in the 1840s, and the interiors of both provinces were infested with banditry. Many individuals have long suspected that the hudiedao were in fact associated with these less savory elements of China’s criminal underground. Butterfly swords, either as a pair or a single weapon, are sometimes marketed as “river pirate knives.”

The Armory of the Wang-Ho as seen on an early 20th century postcard. Note the Hudiedao in the rack on the back wall. Source: Author’s personal collection.

Perhaps it would be more correct to note that these versatile short swords were an ubiquitous part of Chinese maritime life. In a period account describing (in great detail) the outfitting of typical Chinese merchant vessels we find the following note:

The armament is as follows: one cannon, twelve pounder, one do., six pounder; twelve gingalls or small rampart pieces, on pivots; one English musket; twenty pairs of double swords; thirty rattan shields, 2000 pikes, sixty oars; fifteen mats to cover the vessel, two cables, one of them bamboo, and the other coir, fifty fathoms long, one pump of bamboo tubes; one European telescope: one compass, which is rarely used, their voyages being near shore.

R. Montgomery Martin, Esq. 1847. China; Political, Commercial and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty’s Government . Vol. I. London: James Madden, 8 Leadenhall Street. p. 99

As Chinese sailors and immigrants traveled to new areas they brought their traditional arms with them. Early observers in the American West noted that these weapons were often favored by the Tongs, gangs and drifters who monopolized the political economy of violence within the Chinese community.

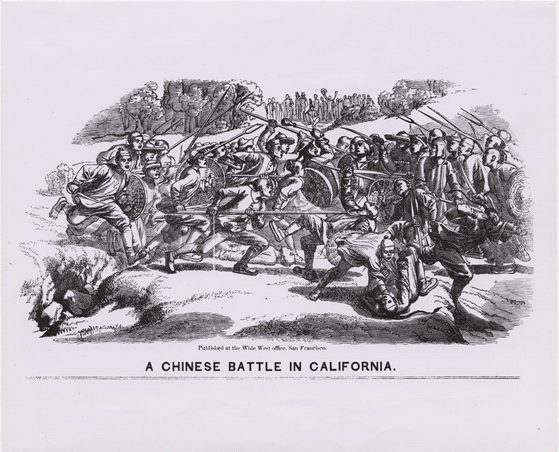

The Bancroft library provides the earliest evidence I have yet found for hudiedao-type weapons in an engraving produced by the “Wild West Office, San Francisco.” This picture depicts a battle between two rival Tongs (communal organizations that were often implicated in violence) at Weaverville in October, 1854. Earlier that year the two groups, Tuolomne County’s Sam Yap Company and the Calaveras County Yan Wo Company, had nearly come to blows.

Both groups closed ranks, began to order weapons (including helmets, swords and shields) from local craftsmen, and spent months drilling as militia units. However, the two sides were far from evenly matched. The Sam Yap Company ordered 150 bayonets and muskets in San Francisco and hired 15 white drill instructors. The Yan Wo Company may also have had access to some firearms, but was generally more poorly provided.

Period accounts indicate that about 2,000 individuals (including the 15 western military advisers) clashed at a place called “5 Cent Gulch.” The fighting between the two sides was brief. After a number of volleys of musket fire the much more poorly armed Yan Wo Company broke ranks and retreated. Casualty figures vary but seem to have been light. Some reports indicate that seven individuals died in the initial clash and another 26 were seriously wounded.

The conflict between these two companies was a matter of some amusement to the local white community who watch events unfold like a spectator sport and put bets on the contending sides. An engraving of the event was sold in San Francisco.

While a sad historical chapter, the 1854 Weaverville War is interesting to students of Chinese Martial Studies on a number of fronts. It is a relatively well documented example of militia organization and communal violence in the southern Chinese diaspora. The use of outside military instructors, reliance on elite networks and mixing of locally produced traditional weaponry with a small number of more advanced firearms are all typical of the sorts of military activity that we have already seen in Guangdong. Of course these were not disciplined, community based, gentry led militias. Instead this was inter-communal violence organized by Tongs and largely carried out by hired muscle. This general pattern would remain common within immigrant Chinese communities through the 1930s.

“A Chinese Battle in California.” Depiction of rival Tongs of Chinese miners at Weaverville in June 1854. Contributing Institution: California Historical Society. Bancroft Library, UC Berkley.

Given that the first known Chinese martial arts schools did not open in California until the 1930s, the accounts of the militia training in Weaverville are also one of our earliest examples of the teaching of traditional Chinese fighting methods in the US. The degree to which any of this is actually similar to the modern martial arts is an interesting philosophical question.

Volkerkunde by F.Ratzel.Printed in Germany,1890. This 19th century illustration shows a number of interesting Asian arms including hudiedao. The print does a good job of conveying what a 19th century arms collection in a great house would have looked like.

The Hudiedao as a Marker of the “Exotic East” in Early Photography

While the origins of photography stretch back to the late 1820s, reliable and popular imaging systems did not come into general use until the 1850s. This is the same decade in which the expansion of the treaty port system and the creation of Hong Kong increased contact between the Chinese and Westerners. Increasingly photography replaced private collections, travelogues and newspapers illustrations as the main means by which Westerners attempted to imagine and understand life in China.

Various forms of double swords occasionally show up in photos taken in southern China. One of the most interesting images shows a rural militia in the Pearl River Delta region near Guangzhou sometime in the late 1850s (Second Opium War). The unit is comprised of seven individuals, all quite young. Four of them are armed with shields, and they include a single gunner. Everyone is wearing a wicker helmet (commonly issued to village militia members in this period). The most interesting figure is the group’s standard bearer. In addition to being armed with a spear he has what appears to be a set of hudiedao stuck in his belt.

The D-guards, quillions and leather sheath are all clearly visible. Due to the construction of this type of weapon, it is actually impossible to tell when it is a single sword, or a double blade fitted in one sheath, when photographed from the side. Nevertheless, given what we know about the official orders for arming the militia in this period, it seems likely that this is a set of “double swords.”

The next image in the series confirms that these are true hudiedao and also suggests that the blades are of the long narrow stabbing variety. This style of sword is also evident in the third photograph behind the large rattan shield. These images are an invaluable record of the variety of arms carried by village militias in Guangdong during the early and mid. 19th century.

Rural militia in Guangdong, Pearl River Delta, taken sometime during the Second Opium War (1856-1860). Source http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

Another picture of the same young militia group. Luckily the hudiedao of the leader have become dislodged in their sheath. We can now confirm that these are double blades. They are of the long narrow stabbing variety seen in some of the prior photographs. Source http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

A third picture from the same series. Note the long thin blade being held behind the rattan shield by the kneeling soldier. The individual with the spear also appears to be armed with a matchlock handgun. Source http://www.swordsantiqueweapons.com.

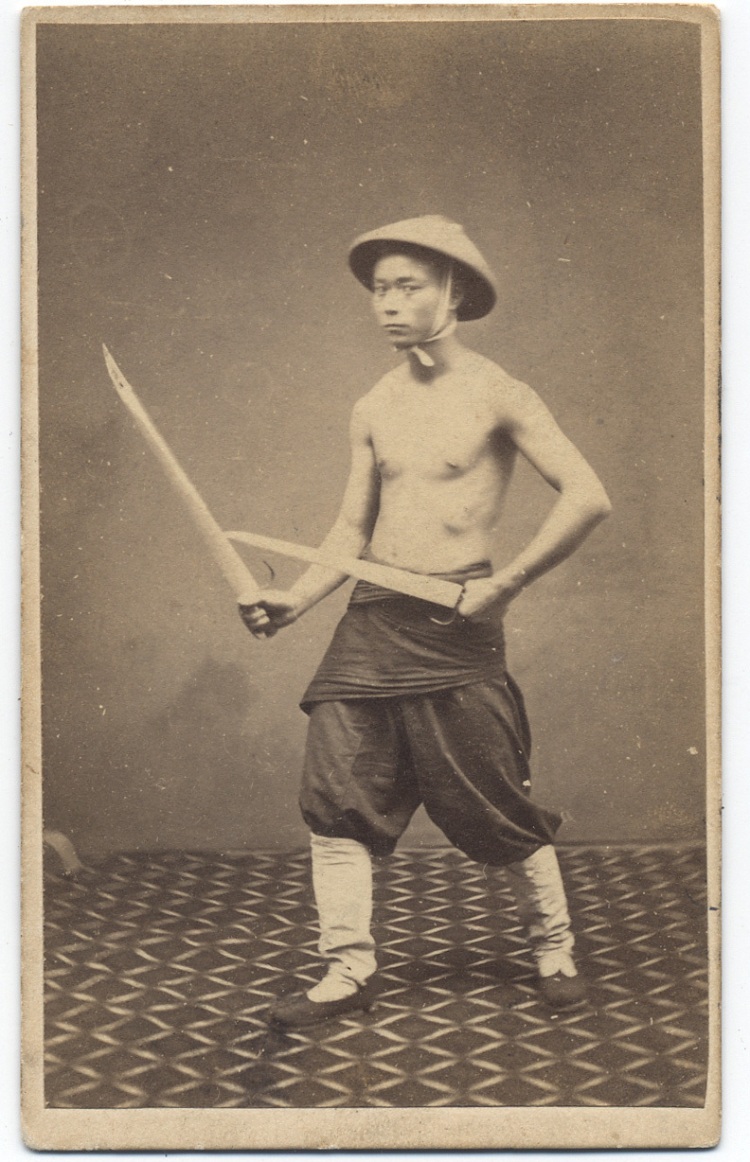

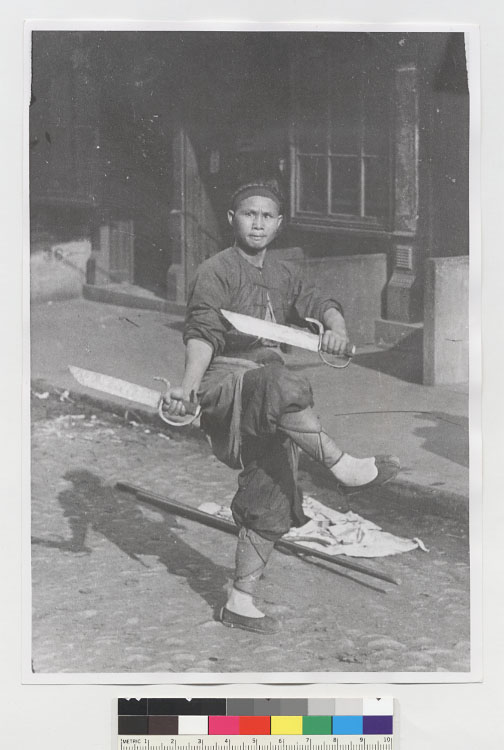

The next photograph from the same period presents us with the opposite challenge. It gives us a wonderfully detailed view of the weapons, but any appropriate context for understanding their use or meaning is missing. Given it’s physical size and technology of production, this undated photograph was probably taken in the 1860s. It was likely taken in either San Francisco or Hong Kong, though it is impossible to rule out some other location.

On the verso we find an ink stamp for “G. Harrison Gray” (evidently the photographer). Images like this might be produced either for sale to the subject (hence all of the civil war portraits that one sees in American antique circles), or they might have been reproduced for sale to the general public. Given the colorful subject matter of this image I would guess that the latter is most likely the case, but again, it is impossible to be totally certain.

The young man in the photo (labeled “Chinese Soldier”) is shown in the ubiquitous wicker helmet and is armed only with a set of exceptionally long hudedao. These swords feature a slashing and chopping blade that terminates in a hatchet point, commonly seen on existing examples. The guards on these knives appear to be relatively thin and the quillion is not as long or wide as some examples. I would hazard a guess that both are made of steel rather than brass. Given the long blade and light handle, these weapons likely felt top heavy, though there are steps that a skilled swordsmith could take to lessen the effect.

1860s photograph of a “Chinese Soldier” with butterfly swords. Subject unknown, taken by G. Harrison Gray.

It is interesting to note that the subject of the photograph is holding the horizontal blade backwards. It was a common practice for photographers of the time to acquire costumes, furniture and even weapons to be used as props in a photograph. It is likely that these swords actually belonged to G. Harrison Gray or his studio and the subject has merely been dressed to look like a “soldier.” In reality he may never have handled a set of hudiedao before.

A studio image of two Chinese soldiers (local braves) produced probably in Hong Kong during the 1850s or the 1860s. This mix of weapons would have been typical of the middle years of the 19th century. Note the hudiedao (butterfly swords) carried by both individuals. Unknown Photographer.

The Hudiedo and the Gun

While guns came to dominate the world of violence in China during the late 19th century, traditional weaponry never disappeared. There are probably both economic and tactical reasons behind the continued presence of certain types of traditional arms. In general, fighting knives and hudiedao seem to have remained popular throughout this period.

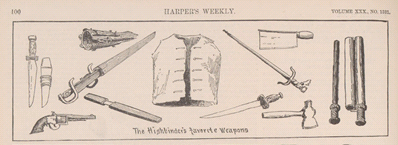

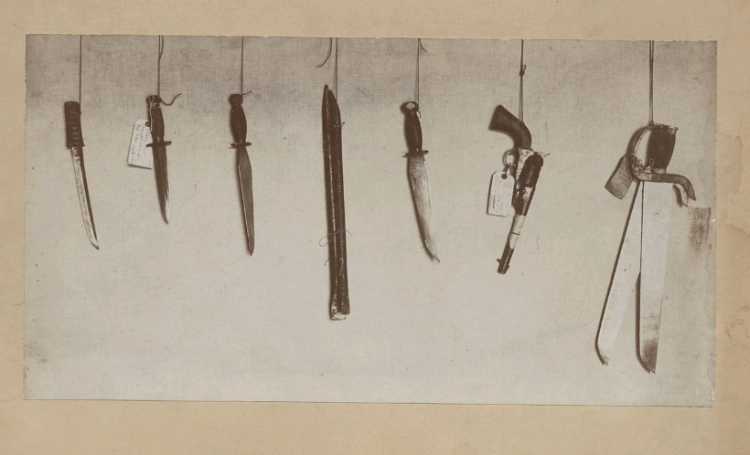

The same trend was also seen in America. On Feb. 13th, 1886, Harper’s Weekly published a richly illustrated article titled “Chinese Highbinders” (p. 103). This is an important document for students of the Chinese-American experience, especially when asking questions about how Asian-Americans were viewed by the rest of society.

Readers should carefully examine the banner of the engraving on page 100. It contains a surprisingly detailed study of weapons confiscated from various criminals and enforcers. As one would expect, handguns and knives play a leading role in this arsenal. The stereotypical hatchet and cleaver are also present.

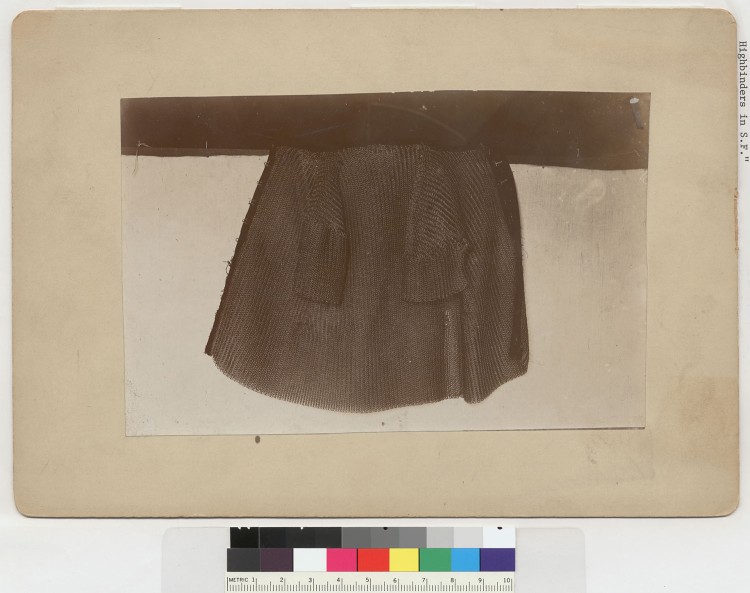

More interesting, from a martial arts perspective, is the presence of various types of maces (double iron rulers and a sai), as well as an armored shirt and wristlets. The collection is finished off with a classic hudiedao, complete with D-guard and shared leather scabbard. It seems that the hudiedao actually held a certain amount of mystic among gangsters in the mid 1880s. The author notes that these weapons were imported directly from China.

“The weapons of the Highbinder are all brought from China, with the exception of the hatchet and the pistol. The illustration shows a collection of Chinese knives and swords taken from criminals, and now in the possession of the San Francisco police. The murderous weapon is what is called the double sword. Two swords, each about two feet long, are worn in a single scabbard. A Chinese draws these, one in each hand, and chops his way through a crowd of enemies. Only one side is sharpened, but the blade, like that of all the Chinese knives, is ground to a razor edge. An effective weapon at close quarters is the two-edged knife, usually worn in a leather sheath. The handle is of brass, generally richly ornamented, while the blade is of the finest steel. Most of the assassinations in Chinatown have been committed with this weapon, one blow being sufficient to ensure a mortal wound. The cleaver used by the Highbinders is smaller and lighter than the ordinary butcher’s cleaver. The iron club, about a foot and a half long, is enclosed in a sheath, and worn at the side like a sword. Another weapon is a curious sword with a large guard for the hand. The hatchet is usually of American make, but ground as sharp as a razor.

The coat of mail shown is the sketch, which was taken from a Chinese Highbinder, is of cloth, heavily padded with layers of rice paper that make it proof against a bullet, or even a rifle ball. This garment is worn by the most desperate men when they undertake a peculiarly dangerous bit of assassination. More common than this is the leather wristlet. This comes halfway up to the elbow, and pieces of iron inserted in the leather serve to ward off even a heavy stroke of a sword or hatchet.” (Feb 13, 1887. Harper’s Weekly. P. 103).

These passages, based on interviews with law enforcement officers, provide one of the most interesting period discussions of the use of “double swords” among the criminal element that we currently possess. These weapons were not uncommon, but they were feared. They seem to have been especially useful when confronting crowds of unarmed opponents and were frequently employed in targeted killings. It is also interesting to note that their strong hatchet-points and triangular profiles may have been a response to the expectation that at least some enemies would be wearing armor.

Desperate men and hired thugs were not the only inhabitants of San Francisco’s Chinatown to employ hudiedao in the 19th century. Both Cantonese Opera singers and street performers also used these swords.

During the early 1900s, a photographer named Arnold Genthe took a series of now historically important photographs of San Francisco’s Chinese residents. These are mostly street scenes portraying the patterns of daily life, and are not overly sensational or concerned with martial culture. One photo, however, stands out. In it a martial artist is shown performing some type of fighting routine with two short, roughly made, hudiedao.

Behind him on the ground are two single-tailed wooden poles. These were probably also used in his performance and may have helped to display a banner. Period accounts from Guangzhou and other cities in southern China frequently note these sorts of transient street performers. They would use their martial skills to attract a crowd and then either sell patent medicines, charms, or pass a hat at the end of the performance. This is the only 19th century photograph that I am aware of showing such a performer in California.

The lives of these wandering martial artists were not easy, and often involved violence and extortion at the hands of either the authorities or other denizens of the “Rivers and Lakes.” Many of them were forced to use their skills for purposes other than performing.

Arnold Genthe collected information on his subjects, so we have some idea who posed for in around 1900.

“The Mountainbank,” “The Peking Two Knife Man,” “The Sword dancer” – Genthe’s various titles for this portrait of Sung Chi Liang, well known for his martial arts skills. Nicknamed Daniu, or “Big Ox,” referring to his great strength, he also sold an herbal medicine rub after performing a martial art routine in the street. The medicine, tiedayanjiu (tit daa yeuk jau), was commonly used to help heal bruises sustained in fights or falls. This scene is in front of 32, 34, and 36 Waverly Place, on the east side of the street, between Clay and Washington Streets. Next to the two onlookers on the right is a wooden stand which, with a wash basin, would advertise a Chinese barbershop open for business. The adjacent basement stairwell leads to an inexpensive Chinese restaurant specializing in morning zhou (juk), or rice porridge.”

Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown by Arnold Genthe, John Kuo Wei Tche. p. 29

Arnold Genthe and Will Irwin. Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown. New York: Mitchell Kennerley. 1913. (First published in 1908). A high resolution scan of the original photograph can be found at the Bancroft Library, UC Berkley).

Dainu’s hudiedao are shorter and fatter than most of the earlier 19th century models that have been described or shown above. One wonders whether this style of shorter, more easily concealed, blade was becoming popular at the start of the 20th century. These knives seem to be more designed for chopping than stabbing and are reminiscent of the types of swords (bat cham dao) seen hanging on the walls of most Wing Chun schools today.

Lin expected his militia to fight the British with these weapons, and the swords shown in G. Harrison Gray’s photograph are clearly long enough to fence with. In contrast, Dainu’s “swords” are basically the size of large 19th century bowie knives. They are probably too short for complex trapping of an enemy’s weapons and were likely intended to be used against an unarmed opponent, or one armed only with a hatchet or knife.

The next photograph was also taken in San Francisco around 1900. It shows a Cantonese opera company putting on a “military” play. The image may have originally been either a press or advertising picture. I have not been able to discover who the original photographer was.

It is interesting to consider the assortment of weapons seen in this photograph. A number of lower status soldiers are armed with a shield and single hudiedao shaped knife. More important figures in heroic roles are armed with a pair of true hudiedaos. Lastly the main protagonists are all armed with pole weapons (spears and tridents).

Cantonese Opera Performers in San Francisco, circa 1900. This picture came out of the same milieu as the one above it. Notice the wide but short blades used by these performers. Such weapons had a lot visual impact but were relatively safe to use on stage.

Cantonese opera troops paid close attention to martial arts and weapons in their acting. While their goal was to entertain rather than provide pure realism, they knew that many members of the audience would have some experience with the martial arts. This was a surprisingly sophisticated audience and people expected a certain degree of plausibility from a “military” play.

It was not uncommon for Opera troops to compete with one another by being the first to display a new fighting style or to bring an exotic weapon onstage. Hence the association of different weapons with individuals of certain social classes in this photo may not be a total coincidence. It is likely an idealized representation of one aspect of Cantonese martial culture. Fighting effectively with a spear or halberd requires a degree of subtlety and expertise that is not necessary (or even possible) when wielding a short sword and a one meter wicker shield.

We also know that the government of Guangdong was issuing hudiedao to mercenary martial artists and village militias. Higher status imperial soldiers were expected to have mastered the matchlock, the bow, the spear and the dao (a single edged saber). While many surviving antique hudiedao do have finely carved handles and show laminated blades when polished and etched, I suspect that in historic terms these finely produced weapons there were probably the exception rather than the rule.

Confiscated weapons. Shanghai Municipal Police Department, 1925. University of Bristol, Historical Photographs of China.

The Hudiedao as a Weapon, Symbol and Historical Argument

Butterfly Swords remained in use as a weapon among various Triad members and Tong enforcers through the early 20th century. For instance, an evidence photo of confiscated weapons in California shows a variety of knives, a handgun and a pair of hudiedao. This set has relatively thick chopping blades and is shorter than some of the earlier examples, but it retains powerful stabbing points.

Chinese Highbinder weapons collected by H. H. North, U. S. Commission of Immigration, forwarded to Bureau of Immigration, Washington D. C., about 1900. Note the coexistence of hudiedao (butterfly swords), guns and knives all in the same raid. This collection of weapons is identical to what might have been found in either China or America from the 1860s onward.

Courtesy the digital collection of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkley.

Chinese coat of mail used by Chinese highbinders in San Fransisco. Contributing Institution: UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. The possibility of meeting a foe wearing armor (also noted in the Harper’s Weekly article) would certainly explain the popularity of strong stabbing points on some 19th century Hudiedao.

Still, “cold weapons” of all types saw less use in the second and third decades of the 20th century as they were replaced with increasingly plentiful and inexpensive firearms. We know that in Republican China almost all bandit gangs were armed with modern repeating rifles by the 1920s. Gangsters and criminal enforcers in America were equally quick to take up firearms.

The transition was not automatic. Lau Bun, a Choy Li Fut master trained in the Hung Sing Association style, is often cited as the first individual in America to open a permanent semi-public martial arts school. He also worked as an enforcer and guard for local Tong interests, and is sometimes said to have carried concealed butterfly swords on his person in the 1920s and 1930s.